Story

Improved Upper Bounds for Slicing the Hypercube

Key takeaway

Researchers developed a more efficient way to slice the n-dimensional hypercube, which has implications for optimizing algorithms and solving complex mathematical problems more quickly.

Quick Explainer

The key conceptual idea is to find a collection of hyperplanes that efficiently "slice" (intersect) all edges of the n-dimensional hypercube. The authors developed a novel edge-weighted hill-climbing algorithm that searches for such hyperplane configurations, leveraging insights from an AI-driven automated search process. Their approach exploits the observation that optimal hyperplane sets may exhibit low-dimensional structure, with groups of hyperplanes sharing identical coefficients. This structured, human-machine collaborative approach led to improved upper bounds on the minimum number of hyperplanes required, representing a significant advancement in understanding this long-standing open problem in discrete geometry.

Deep Dive

Technical Deep Dive: Improved Upper Bounds for Slicing the Hypercube

Overview

This work presents improved upper bounds on the minimum number of hyperplanes required to "slice" (i.e. intersect) all edges of the n-dimensional hypercube. This long-standing open problem in discrete geometry has applications in areas like combinatorics, perceptrons, and threshold circuits.

The key contributions are:

- A new construction that improves the decades-old upper bound of

⌈5n/6⌉hyperplanes to⌈4n/5⌉hyperplanes, except when n is an odd multiple of 5 (in which case the bound is4n/5 + 1). - Techniques for discovering these improved constructions, including a novel edge-weighted hill-climbing algorithm and insights gleaned from an AI-driven automated search process.

- New lower bounds on the maximum number of edges that can be sliced using fewer than n hyperplanes.

Problem & Context

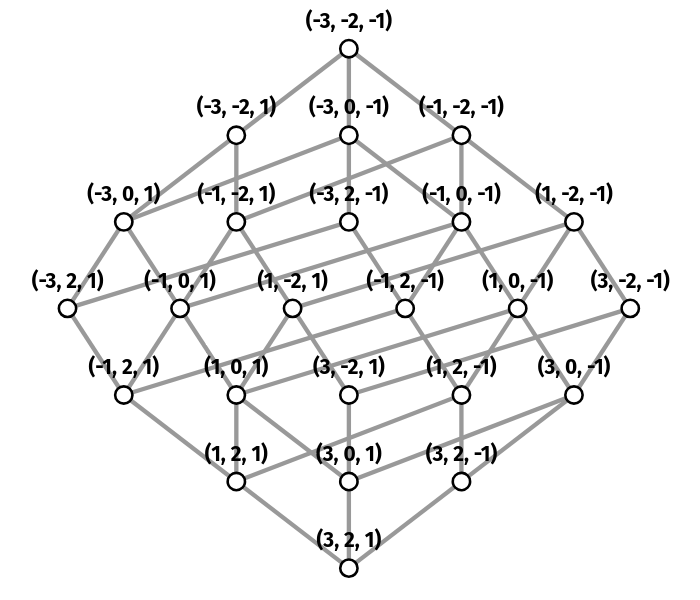

The n-dimensional hypercube Q_n is a graph with vertex set {-1, 1}^n and edge set connecting all pairs of vertices differing by exactly one coordinate. The problem is to find the minimum number S(n) of hyperplanes (linear equations ⟨a, x⟩ = b with a ∈ ℝ^n, b ∈ ℝ) required to "slice" (intersect the interior of) all edges of Q_n.

This problem has been studied extensively in areas like combinatorics, geometry, machine learning, and circuit complexity. The best previously known upper bound was ⌈5n/6⌉ hyperplanes, due to Paterson in 1971. However, the gap between the best known upper and lower bounds on S(n) remained large, motivating the search for improvements.

Methodology

The authors developed a novel edge-weighted hill-climbing algorithm to search for collections of hyperplanes that slice many edges of the hypercube. Key aspects of their approach include:

- Adaptively weighting unsliced edges to help the search escape local optima

- Constraining the search to hyperplanes with groups of identical coefficients, reducing the search space

- Incorporating a variance penalty to encourage hyperplanes to slice similar numbers of edges

- Leveraging a "reduced hypercube" representation to efficiently compute the number of sliced edges

They also made use of the CPro1 automated search system, which utilizes large language models to generate and test diverse candidate algorithms. CPro1 provided valuable insights and partial solutions that the researchers then built upon.

Results

The authors' constructions yield the following improved upper bounds on S(n):

- For

nnot an odd multiple of 5:S(n) ≤ ⌈4n/5⌉ - For

nan odd multiple of 5:S(n) ≤ 4n/5 + 1

This improves upon the previous best bound of ⌈5n/6⌉ hyperplanes.

They also provide new lower bounds on S(n,k), the maximum number of edges that can be sliced using k < n hyperplanes. These improve upon the previous best known bounds for several values of n and k.

Interpretation

The authors' constructions represent a significant step towards a better understanding of the hypercube slicing problem. The highly structured nature of their solutions, with groups of identical coefficients in the hyperplanes, suggests that optimal or near-optimal slicing configurations may exhibit low-dimensional structure.

The success of their approach, combining human-designed algorithms with insights from an AI-driven search process, highlights the potential for human-machine collaboration in mathematical discovery. While the AI alone could not find the new upper bound, the insights it surfaced enabled the researchers to make targeted refinements that ultimately led to the improved result.

Limitations & Uncertainties

While the authors' constructions translate to upper bounds on S(n), they do not prove upper bounds of order o(n) (if such bounds exist). Additionally, their methodology is not applicable to proving lower bounds on S(n) or upper bounds on S(n,k).

It is likely that further progress on this problem will require new theoretical ideas, beyond the combinatorial and computational techniques employed here. The authors note that the determination of the exact value of S(n) remains an open challenge.

What Comes Next

The authors believe that further improvements on the upper bound for S(n) are possible, based on the observation that their current constructions are often very close to fully slicing the hypercube. Formalizing the structural properties of these "good" solutions, and understanding when they exist, could lead to additional breakthroughs.

Additionally, the authors suggest that their work illustrates the importance of human-AI collaboration in mathematical discovery, and that the remarkably structured nature of their solutions may point to deeper insights about the underlying geometry of the hypercube slicing problem.